WIRES AND LIGHTS IN A BOX.

by Christopher Fraser

I wonder what Edward R. Murrow would have made of social media.

“Social media” is shorthand, of course, for the rapid turnover of cultural phenomena, the reduction of earth-shattering events to three second GIFs, and the hysterical obsession with actors, political gaffes and media self-commentary. And I say I wonder because, watching Good Night and Good Luck (2005) again recently—three years after my initial viewing—I was left with quite a different reaction.

Back in 2010, knee-deep in literary fiction and armed with a decidedly jaded view of the Internet as an unwelcome distraction, Murrow’s stark warning that television, as a medium, might be a corrupting influence was intoxicating to me. Contained within Good Night, and Good Luck is the sense of a turning point, with networks beginning to bow to advertisers and chase ratings rather than being led by the dogged pursuit of truth and inspiration. When things begin to fall apart, Murrow’s producer (played with surprising restraint by George Clooney, who also directs the film) murmurs “we might as well go down swinging”, but the implication is that everything that Murrow represents is already being lost.

Nostalgia for a time when newsmen fought for truth and justice—and they were, overwhelmingly, men—is hardly a new idea, and it’s executed brilliantly here. Time goes by, though, and that nostalgia becomes a bit muddied. Good Night, and Good Luck is a brilliant exposé of McCarthyism, but it revels in its own quiet scandal largely because other issues were still under the radar. The first wave of feminism was a tiny blip on the horizon. Laws against sodomy were still enforced across the United States, and would be for at least another couple of decades. Edward R. Murrow had room to breathe, because so many abhorrent laws and attitudes were treated as simple and uncomplicated. We often see the post-war era as a better time because any glimmer of righteous fury was silenced in an instant. Murrow was free to pursue Joseph McCarthy because it fit into the idea of preserving the idea of a utopian USA, rather than actively creating it.

The era that Good Night, and Good Luck portrays was one in which the family television set represented a nightly tradition, a centralised force through which people could reasonably be expected to accept what they were given. This was largely made possible by a notable lack of diverse opinions offered up by the media. There is a sequence during the film wherein the network’s reporters and producers stay up all night, following Murrow’s first unflattering report on McCarthy, to wait for the early editions of the next day’s newspapers. All but one of the responses are flattering, and while this is certainly a good thing for our protagonists within the context of the film, it makes one wonder where debate—in principle, a great tool for cultural reform—might fit in. Despite all the extremity of opinion that comes from our modern access to the internet, the wide-ranging amount of diversity and an ability to join in on national and international conversations can drive momentum, shape stories, and shine a light on topics that Murrow and his ilk would likely never consider.

Of course, for every grassroots social reformer, there’s a hundred One Direction fan bloggers. Rather than flat-out complain about every moron with a keyboard, though, there’s a growing sense that what’s really needed these days is the ability to develop more cultural filters. Everything, now, is at my fingertips; a dozen pictures of adorable cats are suddenly a lot more accessible than a daily newspaper. It’s all a question of selection, though. The thought of paring down a thousand Facebook friends to a small handful isn’t a task I should find especially daunting. Choosing to spend the day reading a novel rather than obsessively keeping up with Twitter feeds shouldn’t fill me with anxiety. Stopping the constant flow of data has become an active choice, rather than something we fall into naturally.

What we often fail to see, largely because it doesn’t come with nearly as loud a fanfare, is that important and engaging media is actually easier to find than ever these days. The problem, though, is that by democratising everyone’s creative power, there’s just as much (and arguably more) meaningless fluff, the type of media that feels like honeycomb—delicious, but disappointingly light. And since we haven’t yet learned how to effectively isolate the excellence from the nonsense, we struggle to develop culturally. In fact, there’s a resurgence of the notion that an idea like developing a discerning eye is somehow elitist, as if Buzzfeed listicles are as fulfilling and important as War and Peace. It’s hard to concentrate on illuminating, sober journalism when a harshly literal interpretation of the word “illuminating” immediately precedes it – flashing lights and captions that provoke a smirk and/or a feeling of total emptiness, luring us away from the stuff that might dare to fill us up.

I found my fiancé through the internet. Not through sifting through dating websites, or scouring Craigslist personals, but through a shared interest in an adventure game released in 1998. There was no single-mindedness in the way we got to know one another, no aggressive pursuit towards a relationship, and I say this because it was all against a backdrop of immediacy – we were a thousand miles apart, each exposed to an endless and rapidly-updated stream of (often inane) information, but somehow found a way to exist within that system and forge something meaningful out of it.

Amongst the noise, I met someone with a fascinating and unique spark, and it wasn’t the first time. Online friends and acquaintances of mine now provide insight and alternative perspectives to me from all around the world. I’ve grown to find comfort in this odd sort of familiarity – one characterised by great physical distance, but often containing just as much emotional power as the relationships I have with people that I see on a day-to-day basis. And I know I’m not alone in this.

Assuming that the Murrow represented in this film corresponds to his real-life counterpart, I have to believe that he would eventually see through all the furious chatter of online activity today and note some valuable developments, both culturally and interpersonally. People have a voice now who were previously stifled – if not maliciously, then by lack of consideration. Granted, now there are billions of wires and billions of lights, and plenty are abused with impunity. Some use the power of open and unrestricted speech to be hateful. Others see a blank page and feel the desperate urge to tell thousands what they ate for breakfast.

Good Night, and Good Luck is bookended by Edward R. Murrow’s speech to the Radio and Television News Directors Association in 1958, warning against a shift towards mindless entertainment. He ends with this:

This instrument can teach, it can illuminate - and yes, it can even inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it towards those ends. Otherwise, it is merely wires and lights in a box.

If every encounter with wires and lights was packed with power and pathos, we would be overwhelmed; screens are omnipresent in a way that Murrow likely never imagined. But moving past that, the fact that the power to create has been so aggressively democratised means that the illuminating, inspiring media he hoped for will always be around, long after every parody Twitter account has burned out in a blaze of idiocy. It is so easy to look at the media landscape today and dismiss it as petty, sensationalist, and often facile; giving billions more people a public platform will tend to do that. But reporters like Murrow are still out there. We just need a keener eye.

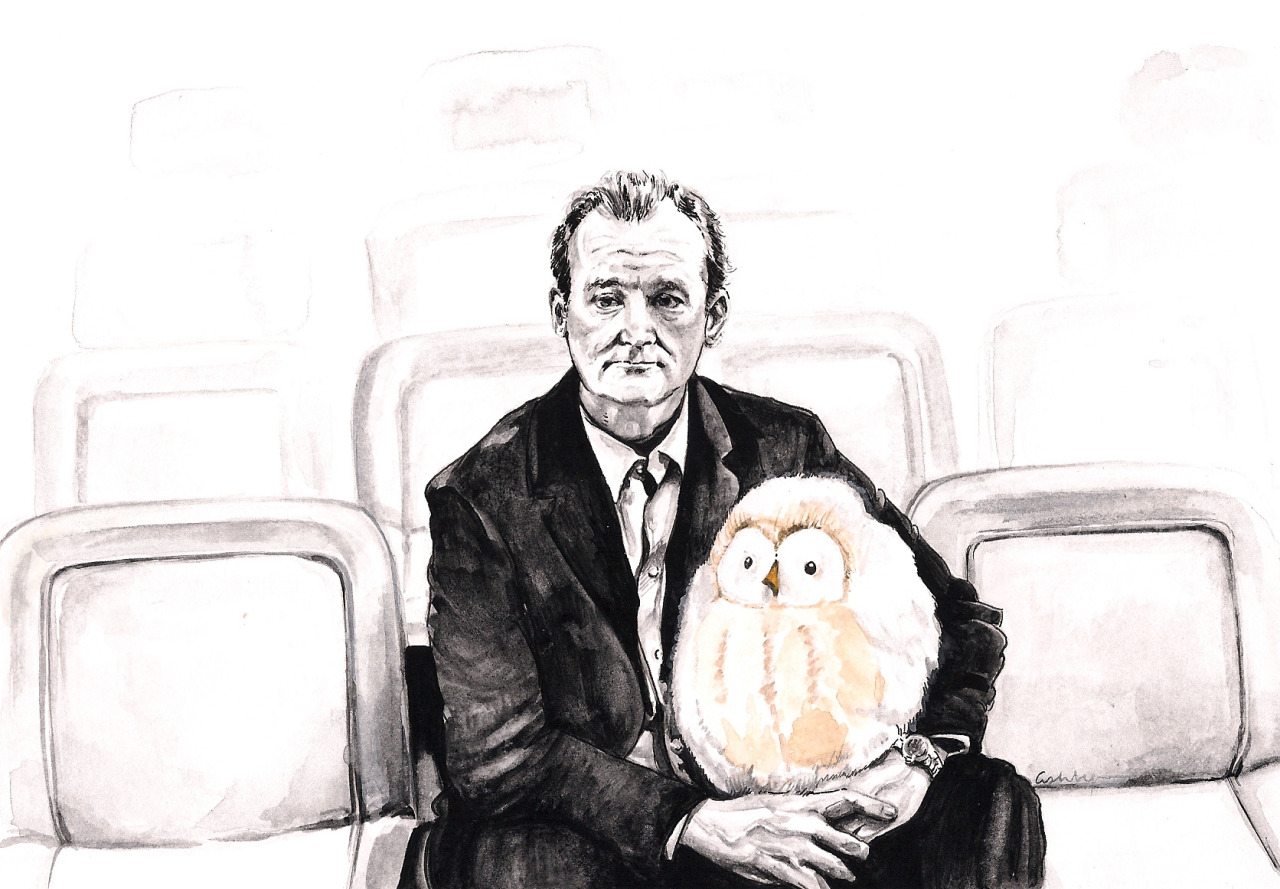

Illustration by Brianna Ashby. This essay originally appeared in Issue 3 of Bright Wall/Dark Room Magazine; you can subscribe to that here.